In art, there is beauty coming from our world. Created by hands gifted from God himself, art has been an invaluable way to measure culture and social commentary. Even when you strip away all outside influences, it is impossible to ignore the intentional decisions made by artists and the conditions that enhanced their decisions.

In 1975, film critic Laura Mulvey created the term “the male gaze”: the representation of women in the arts through the perspective of a heterosexual male. Women tend to be depicted as sexual objects for the benefit of the male viewer. This transcends to any type of art — whether that be film, literature, painting or photography.

In the art sphere specifically, the male gaze has been a precedent, especially in Western art. Historically, most art patrons commissioned men to create art. Art that mirrored their beliefs and highlighted what they most wanted to be portrayed. There was a unifying idea that the artist was a genius — and only men could be at the forefront of what is considered the “genius artist.” It was this construction that was accepted, and therefore, the one that prevailed.

Olympia by Édouard Manet, 1863

Manet’s Olympia garnered tons of controversy when he submitted this painting to Paris’s Salon in 1865. The woman on the bed is a prostitute, yet she is living a decent lifestyle and is able to afford a maid. Manet paints a typical female nude, yet Olympia’s expression is tense, and she is deliberately covering her sex in a non-seductive manner. Olympia invites the viewer to be uncomfortable — to feel shameful that you are perceiving her. You are playing the role of the client, forcefully. While Olympia brings up the discussion of the role of the female nude and attempts to humanize prostitutes, the other side of this is that Manet wanted notoriety, wanted the attention, wanted to make a point and then do nothing about it. It is still a female nude, and it invokes resentment, not change nor pity.

On The Female Nude and Beyond

The female nude is when the male gaze is most glaring. You cannot look away from a body made by a man, for the female nude has been a dominant force in Western art.

“Possession and control are asserted as the natural rights of man. All that can be seen and depicted is viewed as raw material waiting to be taken and exploited,” said Aaron Ziolkowski, who teaches Art History at Penn State. “The male gaze is but one of the many manifestations of patriarchy that pervade every aspect of culture and society.”

The female nude exemplifies possession and control over a woman’s autonomy, and since no female artist could be considered a genius, male artists took control of what they thought was just a muse.

Art is a reflection of society, even when an artist tries to breakaway from outside influence. The female nude and other depictions of women were staggeringly popular in the 19th century, but it was building up to that point. During the Renaissance, quasi-religious imagery and sacred art was embedded into the fabric of the Renaissance, since it came at a time where the wealthy examined their ideas of humanity and the human body’s capabilities itself. Still in the Renaissance you find depictions of nude woman, all in the name of holiness.

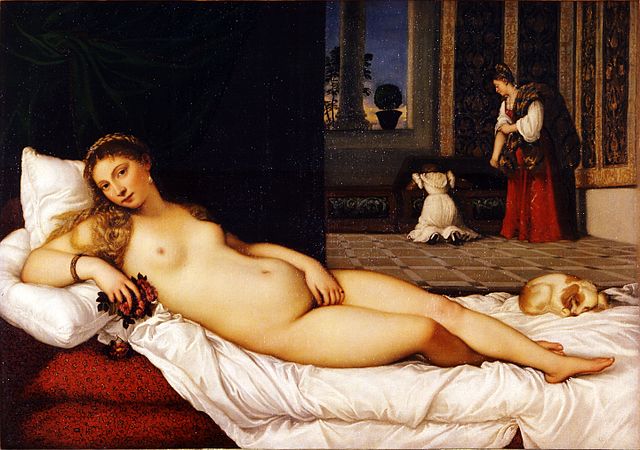

Above is Venus of Urbino by Titian, 1534. She is beautiful, seductive and a clear embodiment of sexuality. Even the title doesn’t name her; the woman is just known as the highest honor of what a woman is. She’s not real, as she is multiple women and fantasies combined into one. This is one of Titian’s most recognizable paintings.

Even today, there has been progress in removing the male gaze from art, but it will always be there as a ghost of the past, haunting the continued objectification of women. Men can freely paint a woman if they feel like they are entitled to her body. If they feel like they own that right. Painting is its own fictitious world, but the edges are blurry when fiction intertwines with the seams of reality.

When looking at the male gaze through the notion of art, it is the perfect way to sum up what privileges allowed for the male gaze to infiltrate into the way that women are perceived. Art has the powerful job of influence, to shape and to re-affirm social constructs already in place.

Follow @VALLEYMag to learn more about art and its history!