Anger, depression and Adderall. Handcuffed to a hospital bed in the suicide watch unit, all Nick could think about was Adderall. How the hell was he going to get his hands on some Adderall?

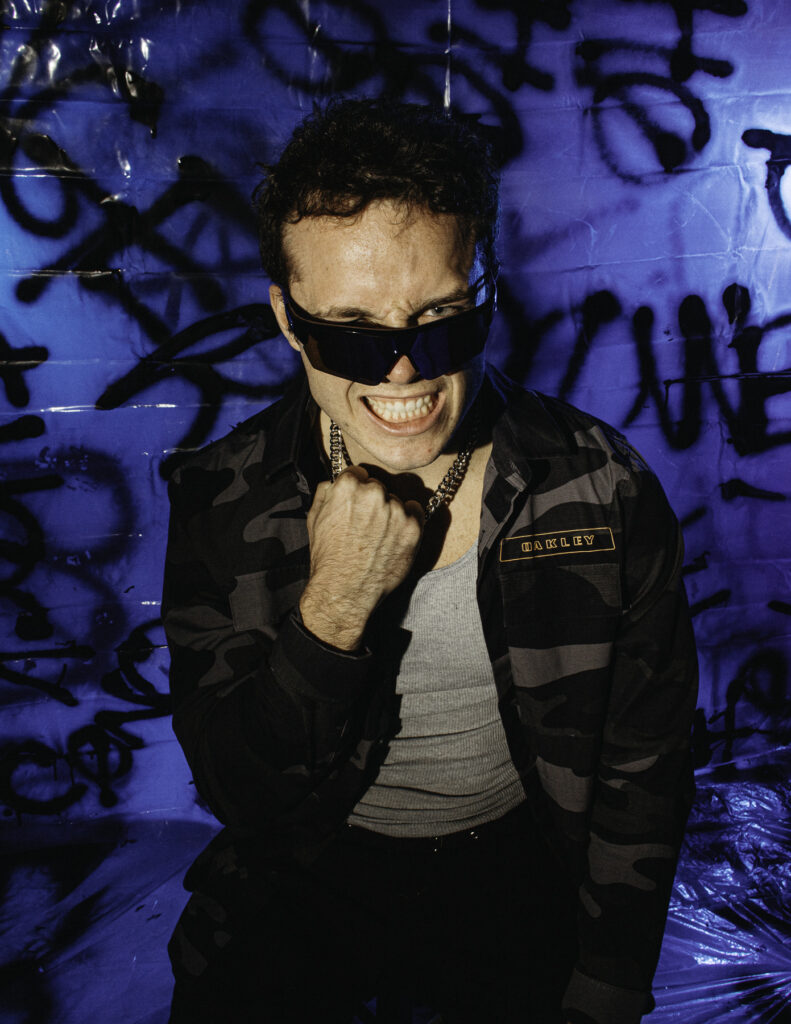

Nick Chermol was a loud kid –– outgoing, smart, athletic, maybe even a bit funny. Sitting with him now, in a room with just a desk and two chairs filled by you and him, that’s still the Nick sitting across the table. He is a 23-year-old who is personable, nonjudgmental and engaged. He plucks his headphones off his head, sets them down on the table and leans back in his chair, making himself comfortable. You wouldn’t know by looking at him what he has survived, but then again, you wouldn’t know one in every 10 guys who look just like Nick walking past you on the street are alcoholics, either.

“You hear a lot of stories of people with addictions having some fucked up shit happen to them; I don’t really have that. That’s still something I’m trying to figure out, like ‘Why? Why do I do this?’” asks Chermol, “It’s really hard.”

Senior year of high school, Nick’s doctor heard a murmur in his heart and confirmed the abnormality as Bicuspid Aortic Valve. Up until then, he was just like all his other friends. Sure, he smoked weed sometimes and yeah, he drank the plastic water bottle filled with his parent’s vodka on the weekends, but he always made it to football practice the next day and still maintained the grades to keep him at his competitive school.

Nick was a varsity athlete, vice president of his class and overall, not someone his parents ever needed to lose sleep over; and they didn’t. With two younger siblings, his parents stayed busy with them, while Nick was left to do his thing and do it well.

Nick’s diagnosis meant no possible future with the sport and no postseason workouts after school. Hearing the doctor confirm that something was wrong was distressing, but that shock also came with a hint of relief. “I finally don’t have to do all this shit,” Nick remembers thinking.

Around that time, his friends decided to try psychedelics. If you asked 18-year-old Nick, he would have said all his friends were also constantly waiting for their next trip. “The second I tried psychedelics, it was always as soon as possible to do it again. You have to wait two weeks in between or else it won’t work — those two weeks,” says Chermol, “I am dying to do it again.”

“I thought my friends were like that too,” Nick says. “It took me until I got sober to realize people don’t think like me.”

Chermol remembers doing acid 10 times, 10 weeks in a row.

“You completely escape everything,” says Nick. “You’re put into a different world. I couldn’t understand why the whole world wouldn’t want to do it.”

Deafening Ticks

It’s high school graduation. Friends crowded into Nick’s home for a night entirely devoted to celebrating their successes. “I basically forced everyone to leave my house,” says Nick. “All I cared about was taking acid.”

Nick tried to convince his childhood friend to take acid with him and the friend wouldn’t budge. But Nick had his mind set on ending the night with that trip, which meant all day long, that’s the only thing that was going through his head. It wasn’t the accomplishments, or the idea of his limitless future that made Nick feel powerful, it was knowing he had a way out of it all at the end of the day.

Throughout the ceremony, the celebratory dinner, the family photos, the speeches, “You could tell I was off,” says Nick. “The day I knew I was going to use, you could just see it in me, I was just waiting to get to that point.” The handshakes, the congratulations, all of it was overpowered by this foot-tapping eagerness to get to the point of the night he was waiting for. The ticking of the clock was getting deafening up until the very moment he got to fully escape into that other world.

The night of high school graduation is normally sealed by some nostalgic tears and a slice of cake; Nick’s came to a close in a hospital gown with an IV pricked into his skin. That acid tab, the illusive white getaway, became the sobering vessel that sent him to the emergency room.

“I was constantly going back and forth from making my parents proud, making myself proud, and just crumbling it,” says Chermol.

“My parents were terrified, but they were way more supportive, I don’t know,” says Nick. “Maybe I just work better with something stricter. I was so angry at everyone, at everything. I was so tired of thinking people had these expectations or I had expectations for myself, and I was just like ‘Who gives?’ I really did not care.”

Incessant Cycles

Nick was a first-year at Penn State going through the motions of a typical Saturday spent in the shadows of Beaver Stadium. “I knew I had to see my dad later, and I asked my friend if he was prescribed Adderall,” says Nick. “I didn’t even think it would get you ‘high,’ I just thought people took it to amp them up to study or focus. I just wanted to be present.”

I wasn’t looking to get this unimaginable high. The second I took it I was like, ‘Oh my god, this is the best shit ever,” says Nick. Nick, from the chair across the table, switching between making eye contact and looking at the wall, tells his story from a bird’s eye view. From this room, he can remember that day being the first time his 19-year-old self thought he may have a problem. That worry manifested as a small knot in his stomach, a minor lump in his throat. On that day, he simply cleared his throat and kept going.

It was State Patty’s day, a few months from the first time Nick experienced the powerful allure of that small capsule of Adderall. It’s a holiday for all Penn Staters, and Nick was doing just what everyone else in State College was doing — drinking. A lot.

Nick paints the picture of him and his friends walking through their freshman year dorm. The beige hallway is brought to life by personalized door decor and posters of upcoming events. One by one, these posters began getting torn to shreds as a Nick, who was too far gone, tried to break through the walls of his freshman year home. Through the sounds of dry wall cracking and the harsher cries of Nick slurring his suicidal thoughts out loud for the first time, his friend dialed 911.

Nick’s addiction was constantly getting caught within cycles. The first being the repetitiveness of trying to tamp down his eagerly addictive mindset. “If I start using a little,” says Nick, “It’s going to be extreme in a couple months.”

The second cycle is the more specific one he would get stuck in daily while using. “When I got too angry or too anxious, I would start drinking to calm down. If I got too low or I wanted to think, I would smoke weed, which would make me paranoid. Then, I would drink and eventually just pass out,” explains Nick. “I would wake up and feel awful and be like ‘Thank god I have Adderall,’ and if I didn’t have it, stay out of my way.”

And these vicious cycles were good at what they did — they were incessant, with so much control and determination that even as Nick sits in that chair now, he still struggles to remember certain things. “It’s hard for me to remember because it’s so terrible,” says Nick, sitting perfectly still, eyes lingering on the wall ahead. “It’s hard to explain how low.”

Nick explains patiently that this is how the brain of an addict functions — it’s constantly tricking you into thinking things weren’t as bad as they were. Your brain purposefully blocks memories so you can’t realize how dire the situation was — how close you were to dying. And maybe during that time Nick knew he was dying, maybe he just didn’t care to live. He was on autopilot, going through the motions day in and day out, and was painstakingly angry for every second of his survival. He was willing to give up the booze, or at least tell people he gave it up, which really just allotted more time devoted to his beloved pills. He wasn’t going to let those go, not while in this cycle.

His girlfriend at the time thought he had lost his mind. Dec. 10 was a Tuesday night, her birthday, but a Tuesday nonetheless, and Nick gifted her a present of 25 Adderall and 25 Xanax pills. “Shit boyfriend of the year right,” Nick jokes. His girlfriend would do the drugs with him, but mainly because she liked Nick, not the highs. Nick picked up the first of the transcending capsules, swallowed and woke up four days later with no pills to be found.

During these four days of a dreary Xanax haze, Nick recalls scalding shower water striking him for hours on end. Cans of Fanta stood upright next to his girlfriend, distraught, shaking back and forth, sobbing on the frigid, wet tile. Hot fog made the bathroom dense, inescapable, cut by the echoes of Nick’s incoherent mumbles through the water.

Christmas Eve, over the chatter of the family gathering and festive music being played, an irritated Nick escaped into the basement as often as possible and drank away his tiredness of a Xanax come down. His family thought he was sober because he claimed to have given up drinking, he may have even thought he was sober so too, but the socializing and the fake conversations were getting to Nick. That week, Nick drank and drank and with each sip got more angry at his surroundings. Picking a drunk fight with his girlfriend in his childhood bedroom filled with trophies and school photos resulted in his dad hearing screams from downstairs. His dad interjected and eventually sat with Nick, nodding his head and keeping his voice calm, as he listened to his grown son who all the sudden seemed just like a little boy again. That Christmas break, the family agreed on an outpatient facility and Nick got sober.

A Bird’s Eye View

The day Nick sits across from you at the table happens to be day 1,001 of his sobriety. He mentions this right at the beginning of the retelling of his addiction, but prefaces everything he says about his sobriety with a disclaimer that in all honesty, he might not know what he’s trying to say.

1,001 days of sobriety, of successfully stifling that villainous voice in the back of his head convincing him that it would just be one beer, and he still doesn’t know if he’s the one who should be giving advice.

The almighty 12-step program of sobriety, brought on by Alcoholics Anonymous, are the steps that make you sit in your addiction, in your anger, in your discomfort and feel the exact weight of it on your chest. Each step pushes you toward success, accountability and helps change peoples lives.

Nick hasn’t done them.

Lots of Nick’s hesitancy has to do with religion, which Nick isn’t too keen on. His sponsor identifies with atheism, which Nick doesn’t exactly resonate with either.

Nick’s sobriety is personal. In the beginning, the journey was about conquering the withdrawals and the imposter syndrome, and now his reflection of the past is more something that prompts the hard questions.

A big question for Nick is, “Why am I so afraid to do these things that I want to do?” Why was he afraid to get sober? Why was he the one to have to get sober when his friends were partying, too? Why would he hold back from pursuing a future doing what he loves, like comedy or podcasting, which he has successfully started as @allcapnobrim, his sobriety and wellness channel, takes off.

Asking these questions doesn’t always have to lead to an answer, and most of the time, it doesn’t. He doesn’t know why he’s more drawn to the extremes than some of his friends, and he doesn’t know how to level out the balance of self-pity versus narcissism that accompanies addiction. He does know that he has been taking it one day at a time, for over a thousand days now, and is “taking the time to see what path I’m on right now.”

“Accepting that you have a problem and you can’t control it was really hard for me,” says Nick. But through that acceptance, Nick gained confidence and a perspective that he did not have before.

“I used to be ignorant to different kinds of people,” says Nick. “But it stopped when I realized I’m not who I thought I was either.” He is more empathetic and he knows he is well-equipped to handle hard situations. He actually handles them — sitting with his feelings and focusing on his reaction — rather than sip, smoke or swallow them.

Nick has, what he calls, “radical accountability,” a better sense of self. He describes himself as creative, more in-control and still pretty loud. In the chair, he is comfortable, calm and taking up more space than he realizes.

He knows he has a story to tell and that acts as the vehicle for his advice. He can tell his story as the man he is now and let whoever is listening draw the comparison from the person he is talking about from that bird’s eye view. His thoughts are clearer up here, less crowded with anxieties, depression or anger. There’s more room for creativity, understanding and growth.

It’s a new cycle Nick finds himself in today: one of invention. He pursues new hobbies, strives for health in all its realms and obsesses over becoming who he wants to be.

“I look forward to the future now,” says Nick as he stands out of his chair and places his headphones back on their rightful spot on his head, “I didn’t used to do that.”

Hey just wanted to give you a brief heads up and let you know a few of the pictures aren’t loading correctly. I’m not sure why but I think its a linking issue. I’ve tried it in two different browsers and both show the same results.

Having read this I thought it was very informative. I appreciate you taking the time and effort to put this article together. I once again find myself spending way to much time both reading and commenting. But so what, it was still worth it!

Its like you read my mind! You seem to know a lot about this, like you wrote the book in it or something. I think that you can do with a few pics to drive the message home a bit, but other than that, this is excellent blog. A great read. I’ll definitely be back.

Your place is valueble for me. Thanks!…

After all, what a great site and informative posts, I will upload inbound link – bookmark this web site? Regards, Reader.

I just like the helpful information you provide in your articles. I’ll bookmark your blog and check again right here regularly. I’m quite certain I will be informed lots of new stuff right right here! Best of luck for the next!

Great post, I conceive blog owners should learn a lot from this site its very user pleasant.

Hi, I think your site might be having browser compatibility issues. When I look at your website in Safari, it looks fine but when opening in Internet Explorer, it has some overlapping. I just wanted to give you a quick heads up! Other then that, fantastic blog!

It is appropriate time to make some plans for the future and it’s time to be happy. I’ve read this post and if I could I want to suggest you some interesting things or tips. Perhaps you could write next articles referring to this article. I wish to read more things about it!